These globally rare communities thrive on very harsh, alkaline conditions--they experience extreme cold in the winter with ice crystals forming in every crack and crevice, extreme heat in the summer, and flooding in spring. In summer the shallow soils bake and dry completely. Some alvars line the lakeshore, subject to wind- and wave-driven ice that scours the rocks.

Not many plants can survive these rough conditions, but those that do don't have much competition! One of the most distinctive alvar plants, and also one of the rarest, is the Lakeside daisy:

Daisy habitat has been preserved in the 19-acre Lakeside Daisy State Nature Preserve. Quarried many years ago, a very thin soil layer has developed on the remaining limestone and is adequate to support many typical alvar plants. Here is a view of the preserve:

On Monday we had the opportunity to visit a naturally occurring alvar in an area that has never been quarried. This field trip was led by some of Ohio's most outstanding naturalists and we got a great introduction to the botany and geology of the area. No, this isn't a parking lot, it is an alvar!

The glacial origins of the alvar's landforms were obvious as we hiked the site. In the photos above and below the striations known as glacial grooves are evident.

In one area, we saw a place where the glacier flowed over and around particularly resistant rock, leaving this formation that locals call "the locomotive":

As the glacier reamed off the upper rock layers, it exposed fossils of marine creatures that were embedded in the limestone. When this rock formed, Ohio was located near our planet's equator and was covered with seawater. Marine organisms thrived in these tropical conditions, and some were preserved as fossils. Here is a horn coral, that was sheared off and its cross section exposed:

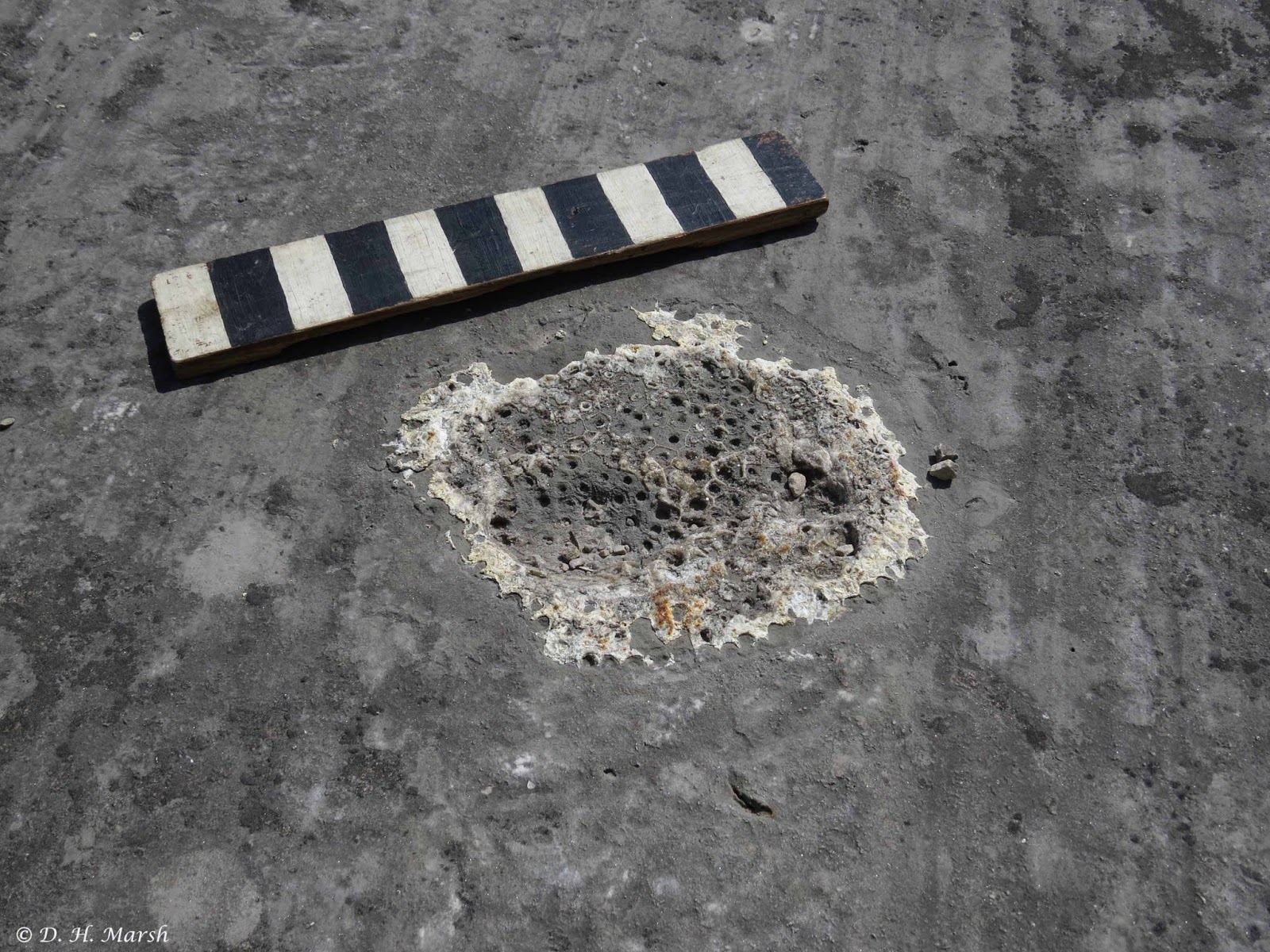

Here is another type of coral; the adjacent ruler is a foot long.

And one more:

Not much grows on the bedrock except in cracks and crevices that trap some windblown soil which eventually builds up enough to support plants. Here is a Lakeside daisy that has survived the alvar's tough conditions:

Some of the other plants that are typical of alvars are eastern red cedar (often stunted), rock sandwort, dense blazing star, and stiff goldenrod.

Very little alvar habitat remains on the Marblehead Peninsula because of the many years of limestone quarrying that has taken place. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources is hoping to preserve some of the area's remaining natural alvar, and this interest is aided by the efforts of the Ohio Natural Areas and Preserves Association (ONAPA), which welcomes new members. I encourage anyone interested in Ohio's natural heritage to join this organization!

Many thanks to Cheryl Harner, Jason Larson, Guy Denny, ONAPA, and all the other Flora-Quest organizers, sponsors and guides for an excellent event!

Your alvar looks very much like Misery Bay on Manitoulin Island, which I was involved we years ago. Flat limestone dipping toward Lake Huron, and masses of lakeside Daisy! Nice to learn of similar habitats.

ReplyDelete